-

1300-1600: Rise and decline of royal Gjetsør Gård in SE Denmark

-

1362: Grote Mandrenke and the opening of the Zuiderzee in the Netherlands

1300-1600:

Rise and decline of royal Gjetsør Gård in SE Denmark

For several thousand years following the termination of the Weichselian glaciation the present sea area connecting The North sea and Kattegat with the Baltic in Southern Denmark was dry land, but the gradual melting of the remaining ice sheets in North America, Greenland and Antarctic brought about a transgression of the former land area between Denmark and Germany about 6-7000 years ago Falster (see 1700-1750: Rostocker Harbour closed by sand on Falster, Denmark).

In the early days of the state of Denmark 1000 years ago the southeastern islands Lolland and Falster was considered a border region hard to control, being exposed to different political influence originating from land areas around the southern Baltic Sea. For that reason, Lolland and Falster at that time did not represent an undisputed part of the Danish kingdom. Danish southern fortifications under King Valdemar den Store (Valdemar the Great; 1131-1182 AD) were therefore constructed along a line north of Lolland and Falster, at Dannevirke, Sprogø, Korsør and Vordingborg, respectively (see geographical location in figure above).

In the following centuries the military and political power changed in Danish favour in northern Europe, with both Lolland and Falster becoming a secure part of the Danish Kingdom. Especially King Valdemar Atterdag (1320-1375 AD) made this development possible, and the new southern national frontier was secured with fortifications at Ravnsborg and Ålholm on Lolland, and by the construction of an impressive Gjetsør Gård near the southern tip of Falster. The first reference to the initial Gjetsør Gård is, however, from 1231 AD.

Gjetsø Gård was constructed at the shore of a fine natural harbour, and almost closed embayment open towards west, about 1 km north of the SW corner of southernmost Falster (see figure below). The buildings at Gjetsør Gård were protected by the construction of a deep moat surrounding the entire site.

The

southern end of Falster seen from NW. To the right the modern town Gedser

with its harbour is seen. The former location of Gjetsør Gård is shown by the

yellow square, and the former natural harbour is indicated by blue colour (today

dry land). The yellow area show the extension of a marine foreland consisting of

a complex of beach ridges, accumulated especially during the Little Ice Age.

Original picture source: Google Earth.

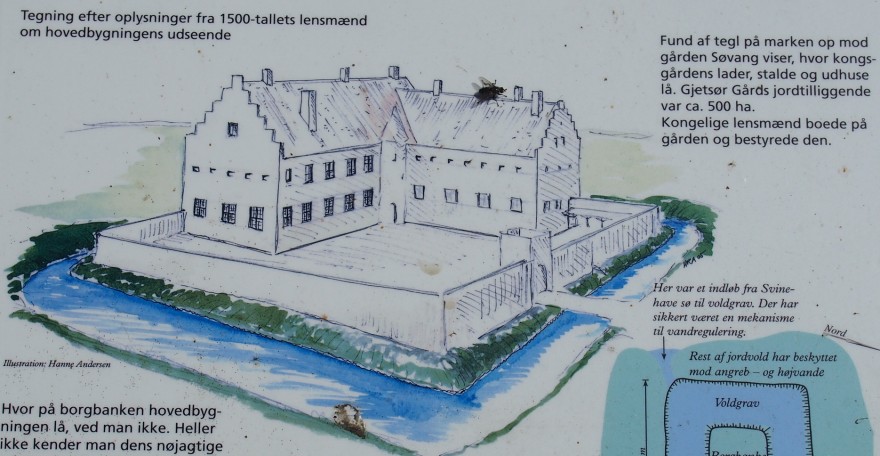

The detailed architecture of buildings at Gjetsør Gård is not known, and presumably the number of buildings and their visual appearance may have changed over time. However, a reconstruction based on written evidence from the mid-16th century suggests the presence of a rather large building complex at that time (figure below).

Reconstruction of Gjetsør Gård in the 16th century, showing the site as seen from SE. Photograph of information plate at the site of former Gjetsø Gård.

The location of Gjetsør Gård proved to be a good one, at least in the beginning. The natural harbour was one obvious reason, and the easy access from north following the crest of the old Weichselian terminal moraine extending throughout southern Falser was another reason. In contrast to harbours in southern Lolland further to the west, this road remained dry and stable even in autumn and winter, while the roads on Lolland often turned into deep mud. As trade with Germany to the south gained in importance natural harbours in southern Falster (including Rostocker Harbour) therefore increased in importance. Often members of the royal Danish family would stay at Gjetsør Gård en route to Germany, while waiting for good sailing conditions. At that time, the crossing to Germany (Rostock) presumably took 6-8 hours in fair weather. Often the travellers had to wait at Gjetsør Gård for 3-4 days before conditions were satisfactory for the crossing, and respectable housing facilities were clearly essential.

Modern

isostatic uplift rates (mm/yr) of Denmark and surrounding regions (Hansen

et al. 2011).

While northern Denmark today still is affected by isostatic uplift following the Weichselian deglaciation, the southern part of Falster is situated within an area of little or no modern isostatic uplift (figure above). In Denmark north of Lolland-Falster several raised former coastlines are therefore today found above the present coastline, but not south of this line. This overall isostatic scheme should protect the fine natural Gjetsør harbour from the unfortunate effects of isostatic uplift, in addition to the overall slow global eustatic sea level rise, but the harbour nevertheless experienced increasing problems with sand accumulating in the harbour inlet during the 14th and 15th century, and especially during the 16th century the harbour gradually lost importance to Rostocker Harbour on the east coast of Falster, only few km’s NE of Gjetsør Gård.

In 1571 AD Queen Sofie to the Danish King Frederik II ordered the building of a Ferry Inn (a ‘ferry kro’) at Rostocker Harbour at Gedesby, to ensure proper lodgement in Gedesby for herself and her family, whenever she wanted to visit her former homeland (Germany). Obviously, the buildings at Gjetsør Gård was now in a bad state, not appropriate for use as night quarter anymore. In 1590 one of the buildings at Gjetsør Gård is reported to be taken down, and no repair works are carried out on any of the remaining buildings.

Finally, the harbour at Gjetsør Gård had to be given up entirely, as the inlet was completely closed by beach ridges. From then on the most important connection between Falster and Germany were operated from Rostocker Harbour (at Gedesby) a few kilometres NE of Gjetsør Gård, on the east coast of Falster.

The reason for the closure of the natural harbour at Gjetsør Gård is therefore not isostatic uplift, but increased coastal transport of sand and gravel along western Falster during the Little Ice Age, due to the increasing frequency of storms and strong NW winds, resulting in the accumulation of a major marine foreland at the SW corner of southern Falster (see figure above), closing the inlet to the Gjetsør Gård harbour.

.jpg)

Remains

of Gjetsør Gård seen towards NW on July 21, 2013. The eastern part of the

former moat is seen in the foreground, and part of the central high where the

buildings were located is seen to the left. The former natural harbour is

located behind the trees to the left. Note person standing on the bridge for

scale. Compare with figure above.

The former Gjetsør Harbour is today located about 1 km inland, mainly because of Little Ice Age coastal erosion and -accumulation. The highway leading to the modern harbour at the town Gedser is located across the former inlet to the harbour (see figure above). The former Gjetsør Harbour itself is still below sea level, but is kept dry by pumping and represents a valuable farming area. Presumably, few people would today recognise one of Denmark's formerly political significant harbours shortly east of the highway to Gedser and its large ferries, heading for Berlin or northern Germany.

Today

nothing remains of the buildings at Gjetsør Gård east of the former harbour.

However, the site is still clearly seen in the landscape (see photograph above),

with well-preserved remnants of both the former moat around the building site,

as well as the entire central high, where the major buildings of Gjetsør Gård

used to be standing.

1346-1349:

The Black Death and the Flagellants

The

Black Death, or the Black Plague, was one of the most deadly pandemics in human

history, widely thought to have been caused by a bacterium named Yersinia

pestis. Shortly after 1300 rumours began to circulate in

The

total number of deaths worldwide from the pandemic is estimated at 75 million

people, worldwide. The total population in

Many

villages were deserted, and remained a widespread feature of

As

in other periods of general distress and trouble, when the Black Death was

raging in Europe, rational behaviour had to step down in favour of blind faith

and simplified, often irrational analyses of cause-and-effect.

Spread of the Black Death across Europe 1346-1949 (left). Victims of the plague (center). Flagellants whipping themselves (right).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1362: Grote Mandrenke and the opening of the Zuiderzee in the Netherlands

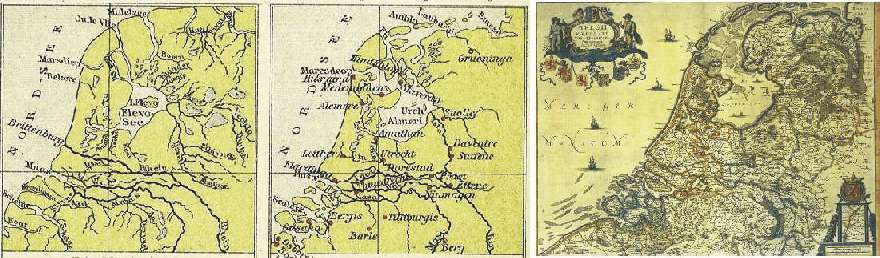

Map showing the outline of the Netherlands with the developing Zuiderzee around year 100 (left) and around year 1000 (centre), according to Tramplers Geographischer Mittelschulatlas, 8th Ed., Wien. The map to the right shows the distribution of land and sea 1658 according to Janssonius Map of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands.

The storm Grote Mandrenke (Great Drowning of Men) strikes the Netherlands in January 1362. Hurricane-force winds with enormous waves and a considerable sea level rise (a storm surge) due to the combined action of push by the wind and lifting of the sea surface because of low air pressure flooded extensive areas of the Netherlands, killing at least 25,000 inhabitants. This number should of cause be seen in relation to the much smaller population at that time than now. The storm also flooded and eroded large land areas in western Slesvig, Denmark, whereby sixty parishes is said to have disappeared totally. Also southern England was severely hit by the storm, with much damage on buildings and infrastructure.

The 1362 storm resulted in severe coastal erosion, contributing to the opening of a pre-existing topographical low in the Netherlands towards the North Sea. This process was already initiated by previous storms, and after a disastrous flood in 14 December 1287 (St. Lucia's flood) the name Zuiderzee came into general usage for this 120 km long pocket-like extension of the North Sea. The 1287 flood is the fifth largest flood in recorded history, and is believed to have drowned somewhere between 50,000 and 80,000 people.

The North Sea itself is also, in geological terms, a new feature in Europe. Following the termination of the last ice age about 12,500 years ago, the present North Sea was dry land. But due to the general (eustatic) sea level rise which followed until about 5000 years ago because of the melting of the last remnants of the big ice sheets in Europe and North America, and the reduction of the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctic, global sea level rose and the North Sea was flooded. Before the North Sea expanded to its present size, a shallow topographical depression existed where the Zuiderzee later formed. Of cause this area had poor drainage, and over time became partly filled with peat. During storms like the Grote Mandrenke this peat was easily eroded, and the North Sea extended rapidly inland to form the Zuiderzee.

Around

the Zuiderzee many fishing villages grew up and several of these developed into

fortified towns with important trade connections with other ports in the Baltic

Sea and in England. The village Amsterdam at the southern end of Zuiderzee was

one of these settlements which later developed into a major city. Later this

trade with base in the Zuiderzee developed with connections to most of the world.

The associated economy formed the basis for Netherlands later period of status

and glory, and the trade activities were also foundation for establishing its

colonial empire.

Zuiderzee (Ijselmeer since 1932) as seen from north (left), and from the southeast (right). The big dam Afsluitdijk can be seen in the centre of the picture to the left. Between this dike and the open North Sea, a complex systems of tidal channels are seen. The distance from the barrier island coastline in the foreground to the innermost part of Ijselmeer is about 120 km. Reclaimed areas, polders, are seen in the foreground of the picture to the right. The city Amsterdam is located at the southern tip of Ijselmeer (the former Zuiderzee). Source: Google Earth.

It was a severe storm with new floodings in 1916 that prompted the early 20th century construction a large enclosing dam to reclaim parts of the Zuiderzee. The construction of this dam, the Afsluitdijk, for the first time made it possible to control changes of water level in the Zuiderzee during storms. With the completion of the dam in 1932 the Zuiderzee became the inland sea Ijselmeer, and large water covered areas could be reclaimed for farming and housing by construction of surrounding dikes and pumping. These newly reclaimed areas are today known as polders.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.