Year 1500-1599 AD

1564: The Nevatters of Mallorca

Satellite picture showing western Mediterranean Sea with Mallorca (arrow). Source: Google Earth

In

1564 the concept of nevater or snowman was fashioned in

As climate was cooling

during the first part of the Little Ice age the

amount of winter snow increased in the mountains of

The nevaters therefore constructed special cases de sa ne, or snow houses, at high altitudes. These snow houses had a special roof construction, which insulated efficiently against warm outside air during spring and summer. Each winter the nevaters filled the houses with compacted snow from the surroundings terrain, and the following summer the snow (now turned partly into ice) was transported to the lowlands. In the year 1699 people on the island Gran Canaria west of Africa would follow suit, beginning to collect snow for cooling purposes.

On Mallorca, the nevaters for long time had a hard, but respected, work. First as late as 1927, the combination of warming following the end of the Little Ice Age and the invention of electrical refrigerators brought an end to the activity of the nevaters.

Left: Nevaters

at work in Mallorca, transporting snow to a snow house in Mallorca. Right:

Remnants of a snow house at 1250 m asl., shortly below the summit of Masanella 1349 m asl., 30 October 2007. Note

person for scale.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

Storms

became frequent in

The

large inland sea

The

storm known as All Saints Floods 11-12

November 1570, however, stand out as a very extraordinary event. This storm

affected most of the

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1576-1578: Martin Frobisher attempts to find the Northwest Passage

Sir Martin Frobisher painted by Cornelis Ketel in 1577 (left). World map used by Frobisher on his first voyage to the Arctic, produced 1569 by the geographer Geraldus Mercator (centre). The map indicates the existence of a broad channel between the New World (North America; lower left) and a continent with four big river systems in the centre of the Arctic Ocean. Frobisher's route from England to Baffin Island (right).

Sir

Martin Frobisher (1535-1594) was

an English seaman who became known for his three voyages to northeastern

In 1576,

at last, Frobisher had gained the necessary funding for his project. He managed

to convince the English merchant consortium the Muscovy

Company, which

previously had sent out parties searching for the

With

the help of Micheal Lok, the Muscovy Company's director, Frobisher was able to

raise enough capital for three small ships: the Gabriel and Michael, of about

20-25 tons each, and a pinnace of ten tons, with a total crew of 35. He set sail

for the

New World

on June 7, 1576. In a storm, however,

the pinnace was lost, and the Michael was abandoned, but on July 28, the Gabriel

sighted the coast of

Frobisher

landed on

During

the following year, 1577, a second and much bigger expedition was prepared. The

English Queen now was very supportive, and sold the Royal Navy ship Ayde to the

expedition (the Company of Cathay) and provided £1000 to cover the expenses of

the expedition. The Company of Cathay was granted a charter from the crown,

giving the company the sole right of sailing in every direction but the east.

Frobisher himself was appointed high admiral of all lands and waters that might be

discovered by him.

With

the three ships Ayde, Gabriel and Michael the expedition left on 25 May

1577

with 150 men, including miners, refiners, a number of gentlemen, and soldiers. Hall’s

Island at the mouth of

The following time was spent in collecting ore, and only little was done in the way of geographical discovery. There was parleying and some skirmishing with the Inuits, and futile attempts were made to recover the five men captured during the first expedition. A couple of Inuits were taken prisoner and brought back to England for display and study.

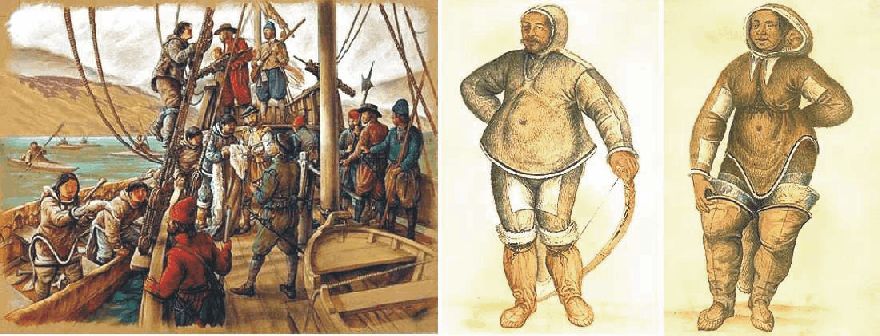

Contact between Martin Frobisher's expedition and the Inuits of Baffin Island (left). Drawings of two Inuits brought back to England (centre and right).

The

return journey was begun on 23 August 1577, and the expedition arrived back in

The

third expedition left Harwich on 30 June 1578, with no less than fifteen vessels.

June 20

Some

attempt was made at founding a settlement, and a large quantity of ore was

shipped. A successful settlement, however, was prevented by dissension and

discontent. On the last day of August, the fleet set out on its return to

Martin

Frobisher still proved interested in economical aspects of life, and later as an

English pirate collected riches from French ships. He was later knighted for his

service in the dispersion of the Spanish

Armada in 1588, under the supreme command of Sir Francis

Drake.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1588: The Spanish Armada destroyed by storm

King Filip II of Spain (left).

The Spanish Armada assembling

at Lisboa, Portugal, in May 1588 (centre). Queen Elizabeth I of

King Filip II ruled

King

Philip II initially had sought an alliance with the

King

Philip II at the same time had an ongoing conflict with Dutch rebels. The Dutch

rebel leader William I, Prince of Orange, was outlawed by Philip and

assassinated in 1584 after Philip had offered a reward of 25,000 crowns to

anyone who killed him. The Dutch resistance forces however continued to fight

on, using their substantial naval resources to plunder Spanish ships and

blockade the Spanish-controlled southern provinces. When

The large Spanish army standing

in the

The Spanish Armada, also known as

the Invincible Armada, was assembled during the spring of 1588. In total 130

ships with 30,000 on board were under command of the Duke of Sidonia, Medina

Sidonia. The fleet set sail

on 28 May 1588 with 22 warships of the Spanish Royal Navy and 108 converted

merchant vessels. The intension was to sail north to the

English

fleet under command of Sir Francis Drake was assembled at Plymouth, awaiting news of Spanish movements. The Spanish Armada was, however,

delayed by adverse weather and did not reach

During the period 20-26 July 1588 several sea battles developed in the Channel region between the Spanish Armada and the English Navy, none of which were decisive. A major problem for the Armada was the lack of secure harbours, where their large ships could obtain supplies of water and other provisions. After all, they had already been at sea for two months. Also the lack of good lines of communication between Philip II and his two commanders at land and sea, respectively, contributed to the awkward situation for the Spanish fleet.

On

the evening of July 27 the Armada was anchored off

In

the shallow waters, the smaller English ships had superior manoeuvrability,

and closed in for battle while maintaining a position to windward (upwind).

Having the windward position enabled the English ships to fire damaging

broadsides into the heeling enemy ships below the water-line. Eleven Spanish

ships were lost or damaged during this action.

The

next day the wind turned southerly, enabling Medina Sidonia to move the Armada

north, into the

Off

the coasts of

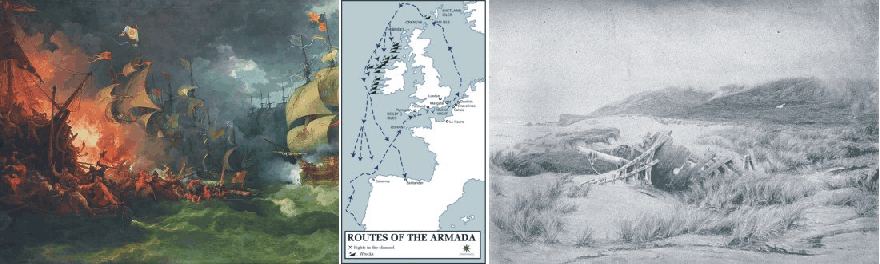

The Spanish Armada being attacked by English fireships in the night between 27 and 28 July 1588. Oil painting by Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg (left). Route taken by the Spanish Armada May-August 1588 (centre). Spanish ship wrecked on the west coast of Ireland August 1588, Illustration from The Art Gallery Illustrated (right).

From an official English

political point of view the outcome was a major triumph for the English Navy and for

Sir Francis Drake. In reality it was a climate-induced disaster for

From a meteorological point of

view the strong westerly and north-westerly winds suggest a major storm centre travelling

across

This British newborn naval sea

dominance was going to be the backbone in the developing

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1520-1600 AD: The Tudor inflation

The index of the purchasing power of builders’ wages in southern England over six centuries (Figure 3 in Brown and Hopkins 1956).

The

profound check on population pressure brought about the Black

Death, and sustained by subsequent bouts of the plague, reduced the pressure

on agricultural resources in Europe for some 150 years (Burroughs,

1997). Although the fifteenth century was not without climatic hardships

(the 1430s being a decade featuring many savage winters in Europe; Lamb

1995) and harvest failures, the recorded incidence of famines was lower than

in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

The

relative abundance of the fifteenth century is excellently illustrated by the

comprehensive work by Sir Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins on wages and

prices in southern England (Phelps-Brown and

Hopkins 1956).This shows (figure above) that the purchasing power of wages,

as represented by those paid to building craftsmen, rose in the second half of

the fourteenth century and remained at high levels until the first decades of

the sixteenth century. They then fell steadily to reach a nadir in 1597, the

year of Shakespeare's Midsummer

Night’s Dream, and then rose very slowly until a more rapid rise

in the early part of nineteenth century. However, the purchasing power of wages

in southern England did not return to fifteenth century levels until late in the

second half of the nineteenth century.

There

are a number of occasional drops in the wage index between 1400 and 1520,

notably in 1439 and 1482, but the overall picture is one of underlying price

stability during this period. This makes the fivefold rise in prices that

started in 1520 so intriguing to economists. Analysis of prices and wages in

France has produced a similar picture.

Known

as the ‘Tudor Inflation’, the rise in prices - and the correspondingly drop

in wage purchasing power - during the sixteenth century has been variously

attributed to demographic pressures and to the influx of gold and silver from

the Americas which inflated the money supply in England. Some has suggested this

development to represent a Malthusian crisis, the effect of a rapid growth of

population impinging on an insufficiently expansive economy (Phelps-Brown

and Hopkins 1956).

Whatever

the reason for the Tudor inflation, this development lead to the so-called Mid-Tudor

crisis between 1547 (the death of Henry

VIII) and 1558 (the death of Mary

Tudor), where English government and society were in imminent danger of

collapse in the face of a combination of weak rulers, economic pressures, a

series of rebellions, religious upheaval in the wake of the English

Reformation, and other factors.

Among

other factors one especially tend to stand out: The Tudor inflation coincided

with a marked cooling of the climate (The Little Ice Age), especially well

documented in NW Europe. The GISP2

ice core from central Greenland adds support to this notion (figure below).

Greenland GISP2 annual delta 18O values. The thin line shows the 5-yr running average, and the thick line represent the 41-yr running average. The period of the Tudor Inflation is indicated by grey colour.

The Greenland ice core data suggests that, although on average not being quite as cold as the later 1650-1750 period, the period of the Tudor Inflation was indeed characterised by recurrent very cold years (spikes indicating low 5-yr average d18O values). In contrast, the preceding period 1390-1520, corresponding to the period of high purchasing power of wages in southern England, was characterised by an absence of such cold spikes. Presumably, recurrent 2-3 cold years in a row during the period of Tudor Inflation may have induced recurrent harvest failures and from this, rising prices.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.