Year 0-1000

300

BC -400 AD: Glacier retreat in the Alps

Großer Sonnblick in southern Austria. Map (left) and photo seen from the south-east (right). The peak seen to the left in the photo is Goldzechkopf, while Großer Sonnblick is to the right.

Many glaciers in the Alps apparently retreated from about 300 BC to about 400 AD (Delibrias et al. 1975). At that time they probably were comparable in size or even less extensive as today, as is indicated by Roman gold mines established high up in the Alps in the Sonnblick area (Austria).

Traffic

over Alpine passes at that time continued even in winter time, and actual

reports of winters in central and northwestern Europe that are recorded from

those times indicate only few that were notable for snows (Lamb

1977).

Gold and Silver have been mined in this region for several thousands of years, and the the Greek geographer Strabo gives the first record for gold mining in the region. Most probably mining activities started in Pre-Roman time like in many other places in the Salzburg region (copper in Muehlbach and salt at Hallein/Duerrnberg).

At Hocharn the mines at the Goldzeche and at Grieswies-Schwarzkogel were most important. The underground workings reached heights of more than 3000m and are considered to be the highest gold mines in Europe.

It

appears that after the collapse

of the Roman Empire in AD 476 some of the mines were blocked by advancing

glaciers, and therefore given up. The entrance to some of these mines are

probably still covered by glacier ice while others have only recently come to

light as the glacier retreated in the 20th century (Lamb

1977, 1995).

However, several of the mine entrances apparently again became free of ice during the Medieval warm period, and in late medieval times the Salzburg region became the world´s largest producer of gold. In the 19th century advancing glaciers blocking the entrance to the mines (many glaciers in the eastern Alps reached their Little Ice Age maximum around 1860) and falling gold price and caused the closure of many gold mines in this region of Austria. Mining finally ceased at the end of World War II.

Nowadays many topographic names remind of the historic gold mining (Hoher Goldberg, Goldzeche, Goldzechkopf, Goldlacklschneid, Pochkar, Silberpfennig, Erzwies, Huettwinkel). Gold can still be found at Hocharn and Großer Sonnblick. The Großer Sonnblick reaches a height of 3,030 m and is the easternmost peak of the Alps that exceeds an altitude of 3,000 metres.

There

are still unmined economic ore bodies beneath both Hocharn and Sonnblick. But as

the impact of gold mining on nature and tourism would be large the gold will

presumably remain in these mountains.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

9

AD: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

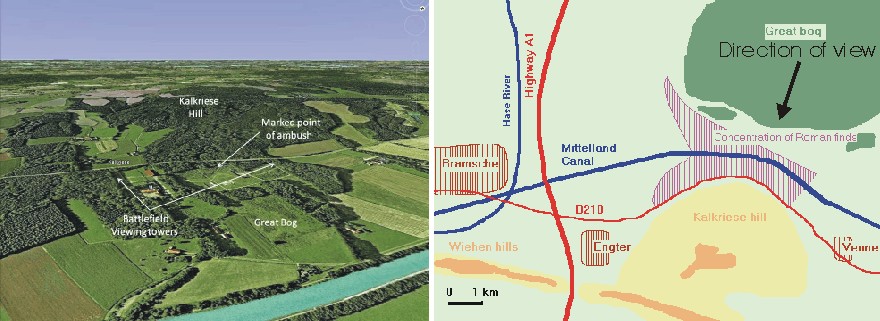

Topography

of Germany (left) with insert showing location of map section to the right.

Detailed map showing the location of the Battle at Teutoburg

Forest (right).

The

name of the Teutoburg

Forest (Teutoburger Wald) in northwestern Germany is connected to one of the

most famous battles from ancient history, the clades

Variana, the defeat of the Roman general Varus. In September 9 AD, a

coalition of Germanic tribes, led by a nobleman named Arminius, defeated a bir

Roman army consisting of three legions and other units, and forced their

commander Publius

Quintilius Varus to commit suicide.

The

result of the battle in Teutoburg Forest was that Germania remained independent

and was never included in the Roman Empire. Presumably the Roman defeat was

indeed one of the most decisive and influential battles in world history.

Weather played no small role in the outcome of this battle.

In

the last decade of the second century BC, the expanding Romans first encountered

Germanic tribes. The Cimbri

and Teutones

were considered dangerous enemies, but ultimately defeated by the Roman

commander Marius in two battles in BC 102 and 101. For two generations, all was

then quiet on the northern front, but in BC 58, when Julius

Caesar was waging war in eastern Gaul,

he got involved in a conflict with the Germanic leader Ariovistus.

At Colmar,

Caesar defeated his enemy, and Caesar subsequently bridged the Rhine and invaded

the country east of the river, which he called Germania.

Following

his successful campaign, Caesar declared the river Rhine as a natural boundary

between the Gallic barbarians ("Celts") and the Germanic tribes, which

in his official opinion were even more barbarous. In reality, Caesar needed a

well-defined theatre of operations and the Rhine was, from a military point of

view, a fine frontier. But from a cultural or ethnic point of view, it was not a

natural frontier at all. The Celtic

culture also existed on the east bank of the Rhine, and people speaking a

Germanic language had already settled on the west bank.

In

BC 39-38, Marcus

Vipsanius Agrippa was governor of Gaul, and fought a war on the east bank of

the Rhine on behalf of the Ubians

against the Suebians,

a Germanic tribe that was notorious for its aggressiveness. After this campaign,

Agrippa resettled the Ubians on the west bank of the Rhine, and founded Cologne.

The Rhine was now changing into being a frontier between an increasingly Roman

Gaul and an increasingly Germanic Germania.

During

this dynamic age, the tribes of the east bank sometimes raided the Roman empire

west of the Rhine. This happened in the winter of BC 17-16, where the governor

of Gallia

Belgica, Marcus

Lollius, was defeated by the Sugambri.

At this occasion the Fifth legion Alaudae lost its eagle standard: the ultimate

disgrace to a Roman army unit. The emperor Augustus

then understood that the Rhine frontier was still highly unstable and therefore

sent his adoptive son Drusus to the north, to pacify the region and create a

more stable frontier.

In

the years BC 16-13, the Romans reorganized the strip of land along the Rhine.

The region now became a military zone, where the army of Germania

Inferior defended the Roman Empire against invaders from Germania. A second

army group was called the army of Germania

Superior was stationed further south along the Middle Rhine. In the summer

of BC 11, Drusus managed to reach the river Elbe with his army. However, on his

way back home, he fell from his horse and died. The Roman conqueror of Germania

was only 29 years old.

Drusus

was succeeded by his brother Tiberius, a capable general who

held the opinion that Germania

was too cold and poor to ever represent a valuable part of the Roman Empire.

On the other hand, the armies could not be recalled immediately after the death

of Drusus, as this would look as if the Romans had been defeated. In the years

BC 9 and 8, Tiberius therefore attacked the Sugambri

and deported thousands of

them to the west bank of the Rhine.

After

this operation all now seemed quiet for a while along the upper reaches of the Rhine, and

in AD 4, Augustus ordered Tiberius to advance northeast again, to finish

the conquest of Germania. The whole of Germania was to become a normal,

tax-paying province, cold climate or not. The army of Germania Inferior

therefore was ordered to march from the Rhine to the sources of the river Lippe,

where a camp was built at Anreppen. Next year, the legions had a rendez-vous

with the Roman navy at the mouth of the Elbe, and Tiberius marched with his army

along the Elbe, which was to become the new northeastern frontier of the Roman

Empire.

Meanwhile, the army of Germania Inferior was commanded by Publius Quinctilius Varus, one of the most important senators of his age and a personal friend of Augustus. Varus was ordered to make a normal province of the country between the Lower Rhine and Lower Elbe, and indeed had some initial success in doing this. Then, everything suddenly went wrong, probably because Varus decided to impose tribute in the new Roman Province.

The

taxes imposed by Varus provoked resistance among a population that had at first

been willing to accept Roman rule, but was not prepared to pay this amount of

tribute. Presumably Varus did not take the gathering storm seriously, and as

usual sent smaller groups of Roman troops to various places in Germania, which

asked for them for the alleged purpose of guarding various positions, arresting

robbers, or escorting provision trains. Thereby

Varus did not keep his legions together, as would have been the proper procedure

in a hostile country.

Next

there came an uprising, first on the part of those who lived at large distances

away from the Roman headquarter, deliberately so arranged, in order that Varus

should march against them and so be more easily overpowered while proceeding

through what was supposed to be friendly country. Varus, on hearing the first

news about the revolt of a far-away tribe, sensibly decided to regroup his army

before taking any action.

All

sources agree that the Germanic leader of the uprising was Arminius, a member of

the Cheruscan tribe and until then a loyal supporter of Rome. The rebels (or

freedom fighters) must have made their

preparation during the late summer of 9 AD. However, not all Germanic leaders

agreed with Arminius' policy, and his plan was apparently betrayed to Varus.

What happened next is not entirely clear. Presumably Varus refused to listen,

and instead rebuked the person(s) that could have saved him.

The battle in Teutoburg Forest took place in the year 9 AD, most likely in September. The battles final stage took part at the northern foot of the Kalkriese hill, a site remarkably well-suited for an ambush. Although only 157 meters high, the Kalkriese is difficult to pass on its northern slope, because a traveller then has to cross many deep brooks and rivulets, and in the level terrain north of the Kalkriese extends a difficult wetland for large distances. However, in between this great bog and the hill exists a more accessible zone up to several hundred meters wide, consisting of stable, Quaternary sandy deposits. The most accessible part of this corridor has a width of only 220 meters. It therefore comes as no big surprise that much later, in the 19th century, German engineers choose this natural east-west corridor along the northern slope of Kalkriese for the construction of both the main road B218 and the Mittelland Canal further to the north.

In September 9 AD, Varus' forces included three legions (Legio XVII, Legio XVIII, and Legio XIX), six cohorts of auxiliary troops (non-citizens or allied troops) and three squadrons of cavalry. The Roman forces were not marching in combat formation, and were interspersed with large numbers of camp-followers.

As

they entered the forest shortly northeast of the modern town Osnabrück, they

found the forest track narrow and muddy, and at the same time a violent

rainstorm began. Apparently Varus neglected to send out advance reconnaissance

parties, but instead advanced with all his forces along the narrow track in one

long formation.

Overview

illustration of the Kalkriese Battlefield from Mike

Anderson’s Ancient History Blog (left). The Mittelland Canal is seen in

the foreground (direction of view towards SW). Overview

map showing the main features of the battlefield (right).

On this narrow track the Roman line soldiers rapidly became stretched out perilously long; estimates are somewhere between 15 and 20 km in total. The Roman forces were then suddenly attacked by Arminius's Germanic warriors armed with light swords, large lances and narrow-bladed short spears. The Germanic warriors quickly managed to surround the entire Roman army and rained down javelins on the intruders from the surrounding forest.

The German leader, Arminius, had grown up in Rome as a citizen and became a Roman soldier, understood Roman tactics very well and could thus direct his troops to counter them effectively, using locally superior numbers against the dispersed Roman legions. Indeed, the German warriors presumably used a very efficient tactic of isolating individual, manageable parts of the extended Roman column, to defeat them one by one. 1930 years later similar efficient ‘motti’ tactics were successfully employed by the Finnish army against the much bigger Red Army during the Finnish-USSR winter war 1939-40, again assisted by the prevailing weather.

The Roman main force however managed to set up a fortified night camp near Engter, and the next morning the remaining Roman soldiers managed to break out into the open country north of the Wiehen Hills, near the modern town of Ostercappeln. The break-out cost heavy losses, as did a further attempt to escape by marching through another forested area, with the torrential rains continuing.

According

to Cassius

Dio, Roman History (Historia Romana, in 80 books):

They

were still advancing when the fourth day dawned, and again a heavy downpour and

violent wind assailed them, preventing them from going forward and even from

standing securely, and moreover depriving them of the use of their weapons. For

they could not handle their bows or their javelins with any success, nor, for

that matter, their shields, which were thoroughly soaked. Their opponents, on

the other hand, being for the most part lightly equipped, and able to approach

and retire freely, suffered less from the storm.

The

continuing rain prevented the Roman forces from using their otherwise efficient

bows, because their sinew

strings become slack when wet. This rendered the Roman soldiers virtually defenceless

as their shields also became waterlogged and soft.

The

Romans then undertook a night march to escape, but marched into another trap

that Arminius had set, at the foot of Kalkriese Hill north of Osnabrück. There,

the sandy, open strip on which the Romans could march easily was constricted by

the hill to the south, so that there was a gap of only about 2-300 m between the

woods and swampland with high vegetation at the edge of the Great Bog to the

north. The Roman soldiers probably expected nothing at this stage, but were

suddenly attacked on their left flank by part of the Germanic forces hiding in

the swamp. Moreover, the Roman forces found the road ahead blocked by a

fortified trench, and, towards the forest, an earthen wall had been built along

the roadside, permitting the Germanic tribesmen to attack the Romans from cover.

The Roman forces was surrounded on three sides.

The Romans made a desperate attempt to storm the wall to break one part of the Germanic pincer, but failed. The highest-ranking officer next to Varus, Legatus Numonius Vala, abandoned the troops by riding off with the cavalry; however, he too was overtaken by the Germanic cavalry and killed. The Germanic warriors then stormed the field and slaughtered the now disintegrating Roman forces.

Varus

did what the Romans considered the honorable thing: he committed suicide. One

commander, Praefectus Ceionius, shamefully surrendered and later took his own

life, while his colleague Praefectus Eggius heroically died leading his doomed

troops to the bitter end.

Archeological

excavations in the area north of Kalkriese have shown that the staff of at least

one legion was present, and the presence of cavalry and auxiliary infantry is

also attested. There were also noncombatants and perhaps women at Kalkriese

mountain battlefield. In total, around 15,000–20,000 Roman soldiers must have

died; not only Varus, but also many of his officers are said to have taken their

own lives by falling on their swords in the approved manner.

Other

Roman soldiers from Germania had already reached the Rhine, and the news that

something terrible had happened spread upstream along the river. Even in Rome,

the populace was afraid, and the emperor Augustus ordered that watch be kept by

night throughout the city.

According

to Suetonius,

Augustus, 23.4:

He

(Augustus) was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut

neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he could dash his head against a

door, crying "Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!"

The

battle in the Teutoburg Forest had a profound effect on 19th century German

nationalism; the Germans, at that time still divided into many individual German

states, identified with the Germanic tribes as shared ancestors of one

"German people" and came to associate the imperialistic Napoleonic

French and Austro-Hungarian forces with the invading Romans who were destined

for defeat. This was part of the background on which Bismarck,

the

German statesman, could unify numerous German states into a powerful German

Empire under Prussian leadership, and thereby create a "balance of power"

that preserved peace in Europe from 1871 until 1914.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

23-79

AD: Gaius Plinius Secundus and Naturalis Historia

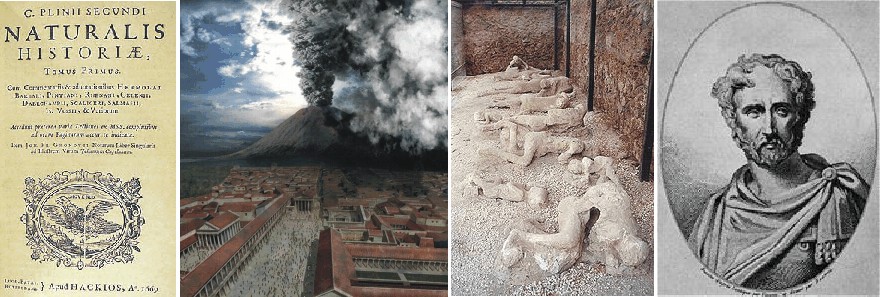

Naturalis Historia, 1669 edition, title page (left picture). The title at the top reads: "Volume I of the Natural History of Gaius Plinius Secundus. Mount Vesuvius during the 79 AD eruption (centre left). Plaster casts of the casualties of the pumice-fall, whose remains vanished leaving cavities in the pumice (centre right). Pliny the Elder (to the right): an imaginative 19th century portrait. No contemporary picture shoving Gaius Plinius Secundus has survived.

Gaius

Plinius Secundus (23 AD – August 25, 79 AD) is also known as Pliny the

Elder. He was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as

naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the

emperor Vespasian. Spending most of his spare time studying, writing or

investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field, he wrote an

encyclopedic work, Naturalis

Historia, which became a model for all such works written subsequently, and

contributed to the survival in Europe of knowledge collected by Aristotle and

his students.

Gaius

Plinius was highly interested in agriculture, which he considered being the

single most important human type of activity. Agriculture depended on correct

planning of seasonal activities, and Gaius Plinius therefore collected much of

what was believed to be known about weather. Much of this knowledge on weather

phenomena is collected in volume two of his Naturalis

Historia, which consisted of no less than 37 volumes in total.

Below

is reproduced (in extract) the English

translation of some examples of Gaius Plinius writings on meteorological

phenomena, all taken from volume two of Naturalis Historia. The Latin version of

volume two can be found here.

Chap. XLII.

I

CANNOT

denie, but without these causes there arise raines and winds: for that certaine

it is, how there is sent forth from the earth a mist sometimes moist,

otherwhiles smokie, by reason of hote vapours and exhalations. Also, that clouds

are engendred by vapours which are gone up on high, or els of the aire gathered

into a waterie liquor: that they bee thicke, grosse, and of a bodily

consistence, wee guesse and collect by no doubtfull argument, considering that

they overshaddow the Sunne, which otherwise may be seene through the water, as

they know well, that dive to any depth whatsoever.

Chap. XLVII.

MEN in old time observed foure Winds only, according

to so many quarters of the world (and therefore Homer nameth no more:) a

blockish reason this was, as soone after it was judged. The Age ensuing, added

eight more; and they were on the other side in their conceit too subtile and

concise. The Moderne sailers of late daies, found out a meane betweene both: and

they put unto that short number of the first, foure winds and no more, which

they tooke out of the later. Therefore every quarter of the heaven hath two

winds apeece...

…The coldest winds of all other, be those which we

said to blow from the North pole, and together with them their neighbour, Corus.

These winds doe both allay and still all others, and also scatter and drive away

clouds. Moist winds are Africus, and especially the South wind of Italie, called

Auster…

…The North wind also bringeth in haile, so doth

Corus. The South wind is exceeding hote and troublous withall. Vulturnus and

Favonius bee warme. They also bee drier than the East: and generally all winds

from the North and West, are drier than from the South and East. Of all winds

the Northerne is most healthfull: the Southerne wind is noisome, and the rather

when it is drie; haply, because that when it is moist, it is the colder. During

the time that it bloweth, living creatures are thought to bee lesse hungrie. …

Chap. LX.

HAILE is engendred of Raine congealed into an Ice:

and Snow of the same humour growne togither, but not so hard. As for Frost, it

is made of dewe frozen. In winter Snowes fall, and not Haile. It haileth oftner

in the day time than in the night, yet haile sooner melteth by farre than snow.

Mists be not seene neither in Summer, nor in the cold weather. Dewes shew not

either in frost, or in hote seasons; neither when winds be up, but only after a

calme and cleere night. Frostes drie up wet and moisture; for when the yce is

thawed and melted, the like quantitie of water in proportion is not found.

Chap.

LXXXVIII.

EVEN

within our kenning and neare to Italie, betweene the Ilands Æoliæ; in like

manner neare to Creta, there was one shewed it selfe with hote fountaines out of

the sea, for a mile and a halfe: and another in the third yeere of the 143

Olympias, within the Tuscane gulfe, and this burned with a violent wind.

Recorded it is also, that when a great multitude of fishes floted ebbe about it,

those persons died presently that fed therof. So they say, that in the Campaine

gulfe, the Pithecusæ Ilands appeared. And soone after, the hill Epopos in them

(at what time as sodainly there burst forth a flaming fire out of it) was laid

level with the plain champion. Within the same also there was a towne swallowed

up by the sea: and in one earthquake there appeared a standing poole; but in

another (by the fall and tumbling downe of certaine hils) there grew the Iland

Prochyta: For after this manner also Nature hath made Ilands. Thus, she

disjoyned Sicilie from Italie, Cyprus from Syria, Eubœa from Bœotia, Atalante

and Macris from Eubœa, Besbycus from Bithynia, Leucostia from the promontorie

and cape of the Syrenes.

Chap.

XC.

NATURE

hath altogether taken away certaine Lands: and first and formost where as now

the sea Atlanticum is, it was sometime the Continent for a mightie space of

ground; if wee give credit to Plato. And soone after in our Mediteranean sea,

all men may see at this day how much hath been drowned up, to wit, Acamania by

the inward gulfe of Ambracia; Achaia within that of Corinth; Europe and Asia

within Propontis and Pontus. Over and besides, the sea hath broken through

Leucas, Antirrhium, Hellespont, and the two Bosphori.

Chap.

XCII.

THE

sea Pontus hath overwhelmed Pyrrha and Antyssa about Mæotis, Elice, and Bura,

in the gulfe of Corinth: whereof, the markes and tokens are to be seene in the

deepe. Out of the Iland Cea, more than 30 miles of ground was lost sodainly at

once, with many a man besides. In Sicilie also the sea came in, and had away

halfe the citie Thindaris, and whatsoever Italy nourseth, even all betweene it

and Sicilie. The like it did in Bœotia and Eleusina.

Pliny the Elder died on August 25, 79 AD, while attempting the rescue by ship of a friend and his family from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that had just destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The prevailing wind would not allow his ship to leave the shore, and after a while Pliny collapsed. His companions attributed his collapse and death to toxic volcanic fumes, although they were themselves unaffected by these gasses.

Gaius

Plinius apparently managed to publish the first ten volumes of Naturalis

Historia

in 77 and was engaged on revising and enlarging the rest during the two

remaining years before his death.

Gaius

Plinius Secundus enjoyed high recognition in Europe long time after his death.

Pliny's encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia was held in high esteem in the

Middle Ages, and were to be printed in no less than 128 editions until 1669 AD.

With all due respect for Pliny the Elder this also to some degree indicates the

lack of significant scientific progress in Europe for more than 1000 years after

the death of Gaius Plinius in 79 AD.

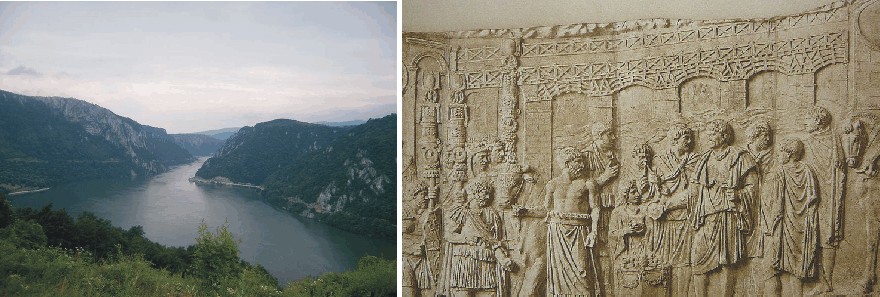

101-106

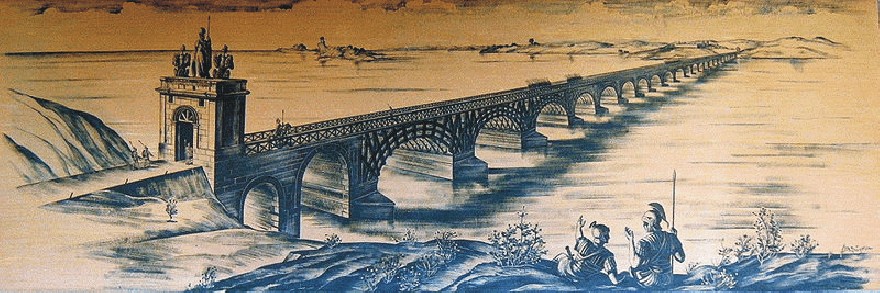

AD: Bridge constructed across the River Danube at the Iron Gate

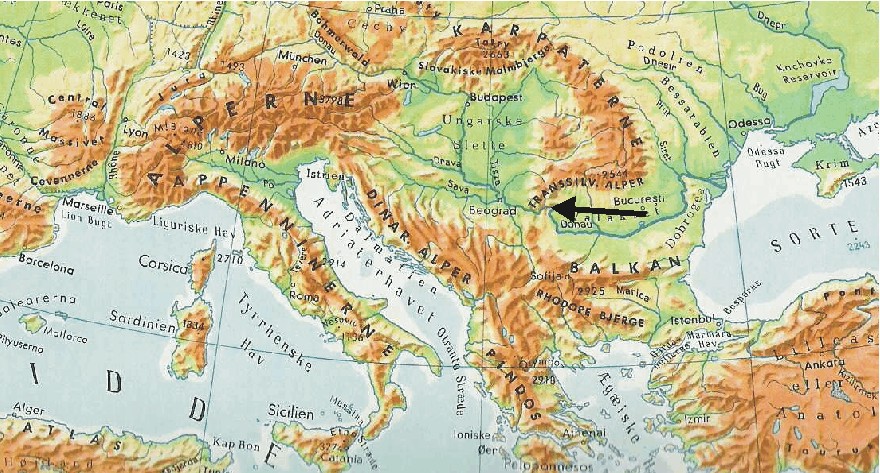

Map

showing the location of the Iron

Gate (black arrow) in south-east Europe.

An

indication of the benign climate of Roman times with a rather long immunity from

cold winters in Europe may be seen in the building between AD 101 and 106 of a

bridge with many stone piers across the River

Danube at the Iron

Gate in south-east Europe, between Serbia

and the Transylvian highlands in Romania

(cf. Lamb 1995).

The bridge was designed by Appolodorus of Damascus for the Emperor Trajan for efficient passage of the Roman armies and administration across the Danube, preceding Trajan's subsequent conquest of Dacia, a large region broadly corresponding to modern Romania and Moldova.

Trajan's bridge apparently stood for no less than about 170 years Lamb (1977, 1995). This must be considered an amazing fact, as in any recent century such a construction would rapidly have been carried away by river ice during a cold winter. In the end the bridge is said to have been destroyed by the Dacian tribes when the Romans later withdrew from this part of Europe (Lamb 1977, 1995).

Artistic reconstruction of Trajan's bridge across the river Danube (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Trajan's

bridge was 1,135 m in length (the Danube is about 800 m wide at the place of

crossing), 15 m in width, and 19 m in height above the average water level. At

each end of the bridge was a Roman castrum,

each built around an entrance to the bridge. In other words, in order to cross

the bridge you had first to pass through a Roman military camp.

For the bridge's construction Appolodorus of Damascus used wooden arches set on twenty masonry pillars (made of bricks, mortar and pozzolana cement) that spanned 38 m each. The entire bridge was built quickly within two years only (between 103 and 105 AD), employing the construction of a wooden caisson for each pier. For more than 1000 years Trajan's bridge was the longest arch bridge ever constructed, in both total and span length, and it apparently survived for no less than about 170 years (Lamb 1975, 1977), before being demolished by the Dacian people. Although representing an impressive engineering feat, relative mild winters with little river ice presumably contributed to the long survival time of the bridge.

A

relief

on Trajan's

Column shows the Roman bridge across the River Danube (see figure below). Noteworthy

on this illustration are the unusually flat segmental arches on high-rising

concrete piers; in the foreground of the relief Emperor Trajan sacrificing by

the Danube can be seen.

The River Danube and the Kazan gorge at its narrowest point (left), and relief showing the Roman bridge across Danube on Trajan's Column in Rome (right). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The

Iron Gate gorge(s) lies between Romania in the north and Serbia in the south. At

this point, the river separates the southern Carpathian

Mountains from the northwestern foothills of the Balkan

Mountains. The Romanian, Hungarian, Slovakian, Turkish, German and Bulgarian

names literally mean "Iron Gates" and are used to name the entire

range of gorges. The Romanian side of the gorge now constitutes the

Iron Gates natural park, whereas the Serbian part constitutes the Đerdap

national park.

The Great Kazan (kazan meaning "boiler") is the most famous and the narrowest gorge of the Iron Gate route (photo above): the river here narrows to 150 m and reaches a depth of up to 53 m (174 ft). Shortly downstream is the site where the Roman Emperor Trajan had the legendary military bridge erected between 103 and 105 AD, preceding his conquest of Dacia. On the right (Serbian) bank of the river a Roman memorial plaque (Tabula Trajana) commemorates Emperor Trajan's military road into Dacia. The Tabula was originally located 50 meters lower than now. The original site was flooded with the construction of a major hydroelectric dam in late 1960s and the monument was moved to a new position just above the waterline. On the opposite Romanian bank, at the Small Kazan, a statue of Trajan's Dacian opponent Decebalus was carved in rock from 1994 through 2004 (see photos below).

Rock carving showing Decebalus on the Romanian side of the Iron Gate (left), and a plate commemorating the roman Emperor Trajan on the Serbian bank (right). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The

twenty pillars carrying Trajan's bridge were still visible in 1856, when the

level of the Danube hit a record low.

In

1979, Trajan's Bridge was added to the Monument

of Culture of Exceptional Importance, and in 1983 it was added to the Archaeological

Sites of Exceptional Importance list, and by that it is protected by

Republic of Serbia.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

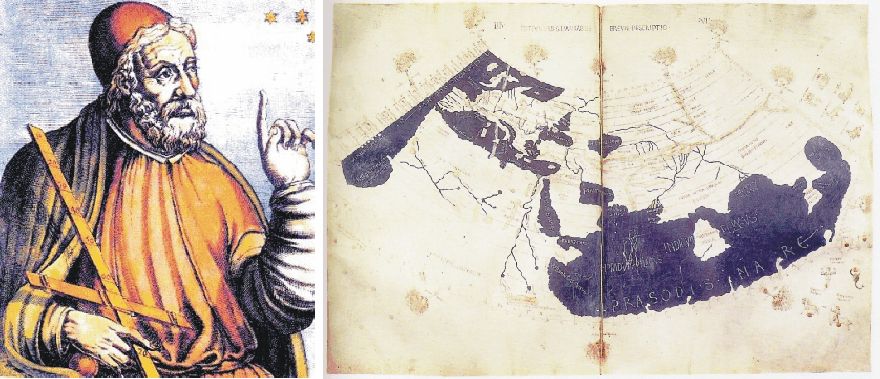

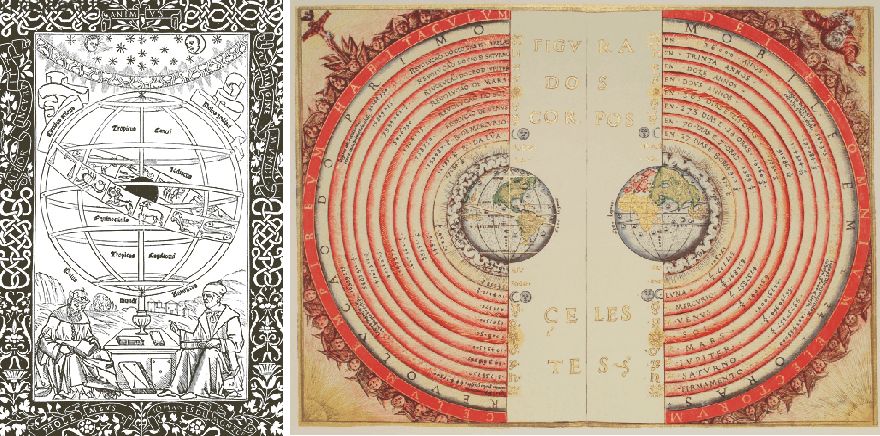

90-168

AD: Claudius

Ptolemaeus

An early Baroque artist's rendition of Claudius Ptolemaeus (left). To the right is shown a 15th-century manuscript copy of the Ptolemy world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy's Geographia, indicating the countries of "Serica" and "Sinae" (China) at the extreme east, beyond the island of "Taprobane" (Sri Lanka, oversized) and the "Aurea Chersonesus" (Malay Peninsula).

Claudius

Ptolemaeus (AD90-168) was a Greek-Roman citizen, who lived in Alexandria,

working at the big scientific library.

He was a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, geographer, and

astrologist. Much of the summary below is adopted

from different sources in Wikepedia

and from Rasmussen

2010, from where additional information is available.

Ptolemy instructing Regiomontanus under an image of the zodiac encircling the celestial spheres (left). Frontispiece from Ptolemy's Almagest, (Venice, 1496). To the right an illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris).

One

of the unique features of the Tetrabiblos,

amongst the astrological texts of its period, is the extent to which the first

book not only introduces the basic astrological principles, but also attempts to

explain the reasoning behind their reported associations in line with

Aristotelian philosophy. Chapter four in Tetrabiblos, explains the "power

of the planets" through their associations with the creative qualities

of warmth or moisture, or cold and dryness. Hence Mars is described as a

destructive planet because its association is excessive dryness, whilst Jupiter

is defined as temperate and fertilising because its association is moderate

warmth and humidity.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

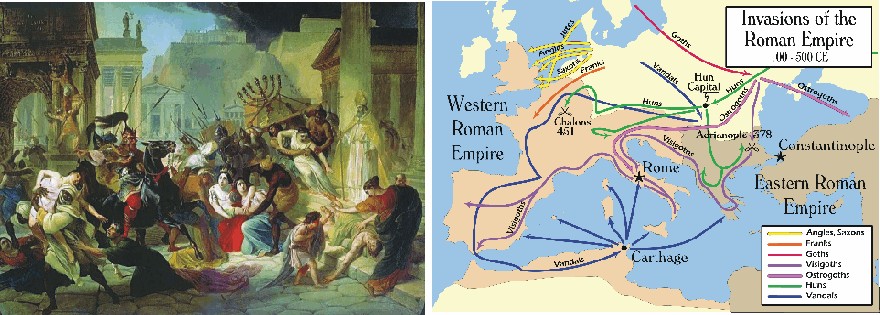

476

AD: Collapse

of the Roman Empire

Karl

Bruillov's 'Sack of Rome' (left). Map of the "barbarian" invasions of

the Roman Empire showing the major incursions from 100 to 500 AD (right).

The

decline of the

Roman Empire refers to the gradual societal collapse of the

Western Roman Empire. This slow decline occurred over a period of four

centuries, culminating on September 4, 476 AD, when Romulus

Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed by Odoacer,

a Germanic chieftain. The following text is based mainly on Büntgen

et al. (2011), Lubick 2011 and Wikipedia.

The

European Middle Ages following the decline of the Roman Empire is important, as

it witnessed the first sustained urbanisation

of northern and western Europe. Many modern European states owe their origins to

events unfolding in the Middle Ages; present European political boundaries are,

in many regards, the result of the military and dynastic achievements during

this tumultuous period.